July 26th, 2009

St. Columba’s Parish,

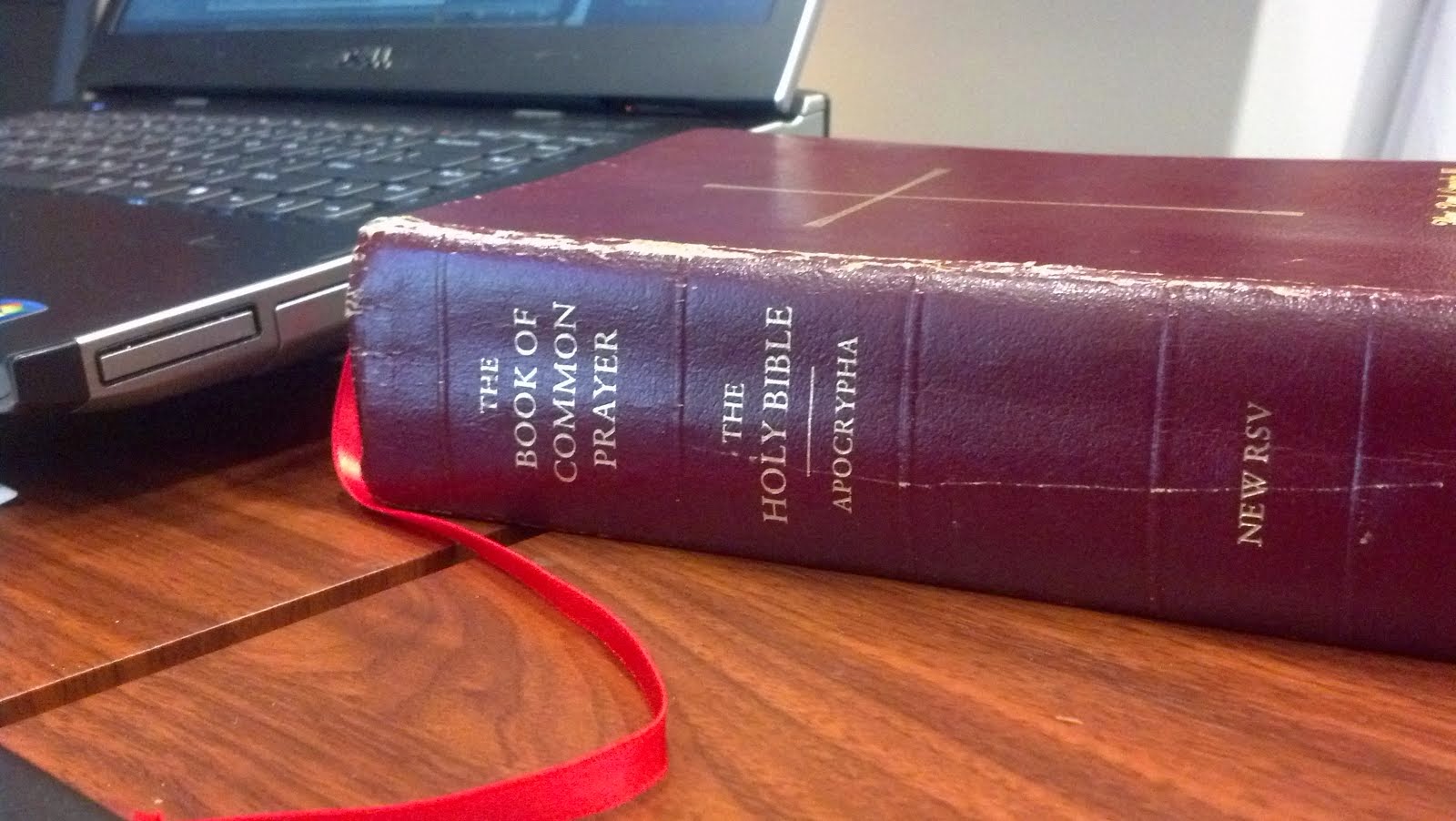

I started writing a letter this week to the group who helped put together the Revised Common Lectionary, which is our source for the schedule of readings we use each week in our worship. The part I like about the RCL is that we hear the Old Testament narrative as a long, week-by-week story, especially during the season after Pentecost. But my curiosity is about today’s Gospel lesson. If you have a Book of Common Prayer printed before about 2007 when the RCL was adopted by the Episcopal Church, and you look on page 908, you’ll see that the Gospel lesson for Proper 12 (today) is Mark 6:45-52. This is Mark’s account of Jesus walking on the water. The RCL editors shifted from Mark to John, and added the beginning of the narrative which is the feeding of the five thousand, and is immediately followed by an account the walking on water story. And my question is why did they do that? Both stories are equally powerful and equally famous. Both stories stand on their own as miraculous acts of Jesus, events that show his power and his glory. So why put them together and ask thousands of preachers to have some sort of consternation about which story to preach?

The story of the feeding of the five thousand is recorded in all four Gospels. And in Matthew’s, Mark’s and John’s accounts, Jesus’ stroll on the

In the first miracle, Jesus provides a non-anxious presence to calm a crowd that, according to some scholars, was teetering on the edge of rebellion against their Roman occupiers. The Jews were overmatched and outmanned, and it would have been a one-sided battle. Instead, Jesus reveals his glory by giving the people what they need versus what the want. The Jews were expecting a messiah who would be a great military leader like King David, someone who would send the Romans back to

In revealing his glory, Jesus is showing that he can fill our worldly and spiritual needs. But the witnesses of this miracle didn’t want to see that. They had their expectations. They knew what they were looking for, and they thought they’d found it in this guy. Instead of seeing the miracle on Jesus’ divine terms, showing that he is the source of life like he showed the Samaritan woman at the well in John 4, the people want to put their own interpretation and implications on what Jesus has done. Instead of seeing Jesus as the one who can bring about fulfillment of the complete range of human needs, the people put their expectations on him that he can do whatever they want him to do.

How often do we do that? How often in our own relationships, not only with God, with our parents, children, spouses, partners, friends or co-workers, do we put our own expectations on those relationships with the other person’s expectations as an after-thought?

He goes away to the mountain, one of his favorite retreat spots, and his disciples head across the water to

Before they could take him in the boat, they were on the other side of the water. This is not a miracle for the sake of having a miracle. It was an act of glory to calm the fears of the disciples. It should be noted that there is nothing saying that the disciples were indeed calmed just because Jesus said, Do not be afraid. But one has to wonder how they felt when they saw their Lord and their teacher standing with them in the midst of the rough waters. I wonder how they felt when they found themselves suddenly in the place where they needed to be. Was Jesus with them the whole time? Had he shown up at just the right moment? Did he know that the winds were going to pick up and they’d be frightened?

What strikes me the most about this part of today’s Gospel is that it doesn’t say that Jesus got them where they needed to be. He said, “It’s me. Don’t be afraid.” The winds may very well have continued to toss the boat around, but the very real presence of Jesus got them to the place they needed to be.

On about Wednesday of this week, I stopped writing my letter to those who wrote the Revised Common Lectionary about why they would have put these two stories together. Instead, I started wondering why we had not put them together before. In this one Gospel lesson, Jesus reveals his glory to those around him, and in his glory, sharing his gifts of grace to give his followers exactly what they need.Ours is a God of abundant love, standing ready to give us what we need, if we will open our hearts to receive that love.

Let us pray: Christ, our brother, we thank you that you know our needs before we can ask. We thank you that you have given us what we have needed and not always what we have wanted. Help us to see your hand at work in the world about us and to know your glory as it is revealed every day. Be with us in the storms of life. Let us know your presence and let your presence calm our hearts. All this we ask in your name. Amen.